Originally appeared in RESIDE Magazine.

When the powerful traveled in pomp between the windswept castles and drafty churches of medieval and Renaissance Europe, tapestries were the preeminent visual art form. Weavers in Flanders and France produced portable masterpieces from the cartoons of leading artists, including Raphael and Peter Paul Rubens. When Henry VIII’s collection of more than 2,450 tapestries was valued for sale during the English Civil War, many were priced at thousands of pounds, well beyond the value of any other item in the inventory.

Since then, textiles have slipped down the hierarchy of art forms. As houses have become warmer, paintings and sculpture have generally taken center stage as decorative and cultural objects. Textiles became synonymous with carpets, curtains and clothing. However, the past century has seen a resurgence of interest among artists in textiles as a creative medium, largely led by women.

When German Bauhaus student Anni Albers was diverted to weaving from glasswork and painting, she transformed the potential and reputation of thread. She fled Nazi Germany in 1933, traveling with her artist husband Josef to the USA, and was honored in 1949 with a show at MoMA (Museum of Modern Art) in New York—the first solo exhibition for a textile artist. As she wrote in her 1971 book On Designing, “Besides surface qualities, such as rough and smooth, dull and shiny, hard and soft, textile also includes color, and, as the dominating element, texture, which is the result of the construction of weaves. Like any craft, it may end in producing useful objects, or it may rise to the level of art.” Her compelling explorations of the limits of the medium take their place in the history of 20th-century abstract art.

Albers became a key figure in the evolving American Fiber art movement, which included pioneering figures such as Claire Zeisler, who produced towering sculptures from knotted and braided threads, and the influential Lenore Tawney, whose free-form installations subverted the typical weaving grid to create fluid patterns. The movement peaked in the 1980s, but an Albers retrospective at London’s Tate Modern in 2018 was just one sign of revived interest in her legacy.

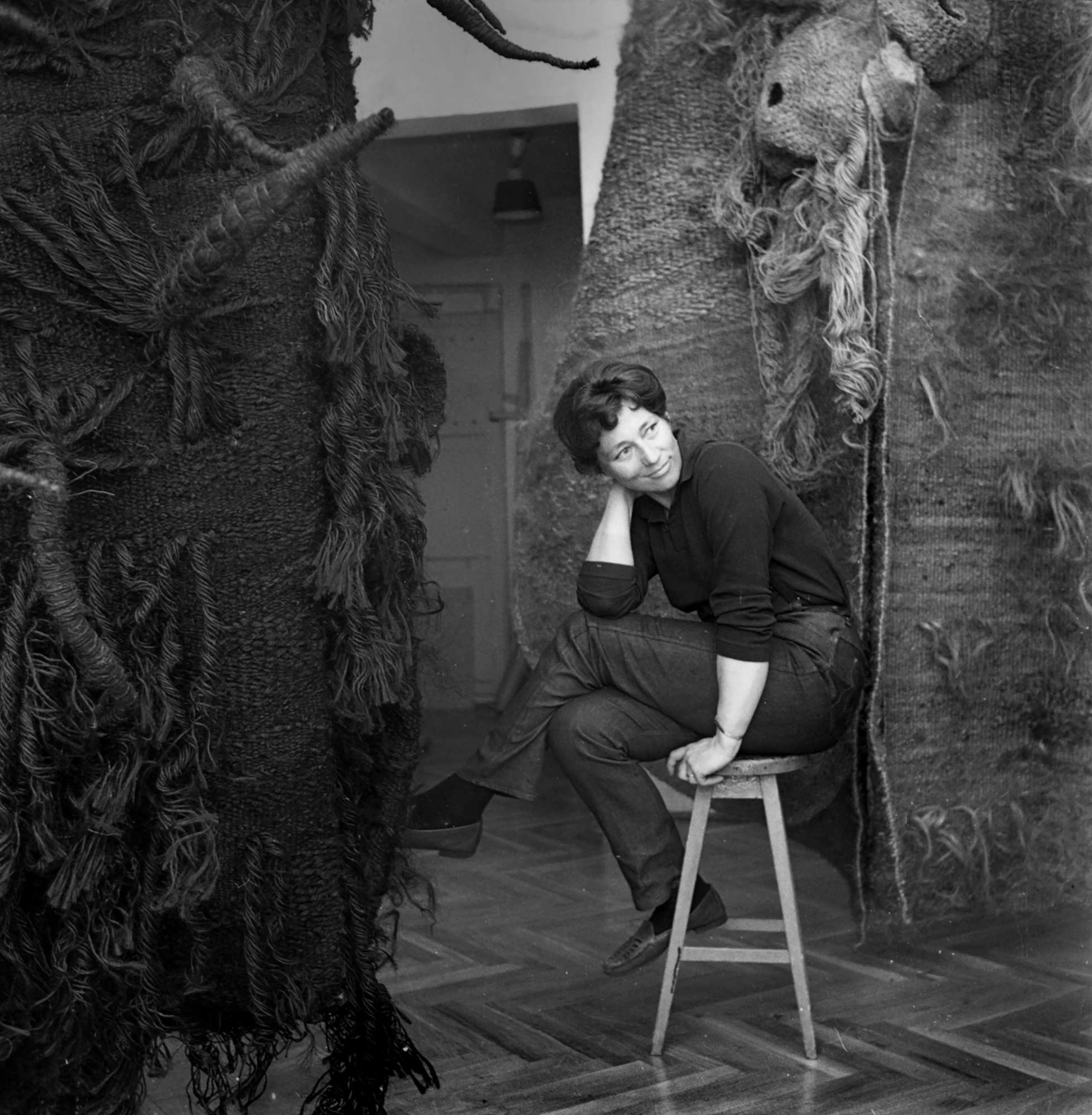

In Europe, meanwhile, Polish sculptor Magdalena Abakanowicz, barred from exhibiting her paintings by the Communist leadership for failing to conform to the Socialist Realist style, was offered a place to work in the studio of weaver Maria Laszkiewicz. She went on to develop groundbreaking 3D works called Abakans, made from coarse sisal, a plant fiber used to make rope and carpets. Initially confusing to critics and collectors, these powerful sculptures, with their enveloping dimensions and visceral textures, have come to be appreciated as fine art. In a 2010 interview, Abakanowicz said: “The Abakans irritated people. They came at the wrong time. In fabric, it was the French tapestry; in art, Pop art and Conceptual art; and here was a huge, magical thing.” In 2016, Abakan Rouge III, 1971, sold for nearly €75,000 at an auction in Poland, while a major Abakanowicz retrospective is taking place at Tate Modern until May 21.

“Like any craft, textile may end in producing useful objects, or it may rise to the level of art”

Contemporaries of Abakanowicz are also finding new fame. Olga de Amaral, who lives and works in Bogotá, produces shimmering gold textiles, partly inspired by the pre-Columbian examples that also influenced Albers, as well as mixed-media hanging works and floor sculptures combining wool and horse hair, linen, gesso, and acrylic paint. She was the focus of the recent touring exhibition Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock, which began at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston before moving to Michigan’s Cranbrook Art Museum in 2021. Through their intensity, her works reflect the focus and time required to create them. She has said: “As I build these surfaces, I create spaces of meditation, contemplation and reflection… Tapestry, fibers, strands, units, cords, all are transparent layers with their own meanings, revealing and hiding each other to make one presence, one tone that speaks about the texture of time.”

Sheila Hicks, meanwhile, studied under Josef Albers at Yale and, aged 84, she delighted audiences at the 2017 Venice Biennale with her mountain of multicolored balls of yarn in the former Arsenale. She says: “Textile is a universal language. In all cultures of the world, textile is a crucial and essential component.” As she points out, the expressive power of the medium is embedded in our language; both text and textile trace their etymology to the Latin word “texere”—to weave.

Behind these pioneers there is a new generation of artists drawn to textile for its potential to communicate. Jacqueline Surdell, who trained as a painter, works with heavy cotton rope and brightly colored yachting cord to create wall sculptures. Building them is physically demanding: she uses her body as a weaving shuttle, carrying kilos of industrial weft in and out of the warp. While her works honor the history of industrial labor in her home city of Chicago, they also explore social constructs. Surdell says she is influenced by “iconic feminist artists who were using textile to question gender binaries and things like that”. These include Harmony Hammond, co-founder of New York’s first women’s cooperative art gallery in New York, and the Indian artist Mrinalini Mukherjee, whose biomorphic forms in hemp and jute often evoke unconventional sexualities.

New York-based Sagarika Sundaram similarly tackles cultural shifts and new identities. Using raw natural fiber and dyes, she engages with the past and present of felted textiles in Central Asian nomadic culture. Her handmade forms often mirror those found in nature, from blood vessels to rivers. She began her career at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, western India, where design was embedded in social awareness. Today, Sundaram combines commercial work—on rugs, for instance—with her fine art practice (on show in Narrative Threads: Fiber Art Today at Houston’s Moody Center for the Arts until May 13). The difference is that “art opens up questions, it opens up a conversation. It’s almost a probe, a gesture that creates a space for something around it,” she says.

In London, the Royal College of Art (RCA) has emerged as an important center for experimentation with textiles. Like Sundaram, Northern Irish artist Mary Little trained in design—specifically furniture. After a move to California, she now works with cut-and-stitched, unbleached cotton canvas to craft evocative pleated and curved hangings. Their pockets of light echo the hills of her native island. Also in London, American Cecilia Charlton enrolled on the RCA’s painting MA in 2018, though it was in embroidery and weaving that she found the most fertile outlet for her interests. Charlton’s layered pieces call on the history of formal abstraction, folk pattern, math, and the cosmos.

Italian artist Bea Bonafini enrolled on the same course in 2014—“to react to the painting world”—and was encouraged to be interdisciplinary. “I had performance, food, and textiles. I had machines from the fashion department. I was getting into ceramics, I was painting on leather. I was making sculptures out of salty bread dough and staining them. I was trying to figure out how to manipulate materials in different ways and not narrow myself down,” she says. Most recently, she has been working with commercially produced domestic carpets, creating densely allusive images using an inlay technique. She is fascinated by the transformation of her material, “because it goes from being something with a horizontal surface to a vertical surface, from something that could be domestic to something of the fine arts—elevating it to this other realm”.

Credits:

Photos: Mary Little Studio; The Estate of Magdalena Abakanowicz and Marlborough Gallery; Courtesy of Bea Bonafini/Bosse & Baum; Cecilia Charlton; Artiq; © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw; Courtesy of the artist and Spazio Nobile/spazionobile.com

![Cecilia Charlton, Somerset [passage of time, sunset], 2021](https://www.sothebysrealty.com/blog-api/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/3-level.jpg)